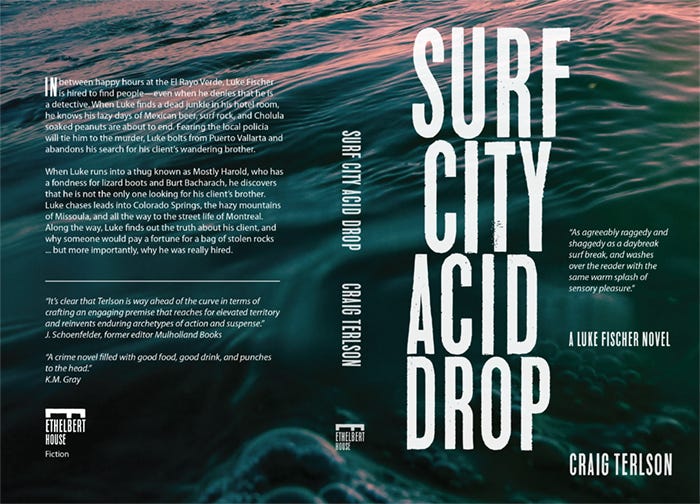

When I decided to re-release the first Luke Fischer novel, Surf City Acid Drop, I wanted to add something for those who have been following the series. The first Luke novel has received a lot of wonderful reviews over the years (as have all three of them.) One writer had a particularly interesting angle on the character, and I always read his reviews with great interest. So when it came time to ask someone to write a new intro for Surf City, my first choice was Thomas Trang.

To my absolute delight, he said yes. I really do love how Mr. Trang reads, thinks, and analyzes. The intro he wrote talks about my character Luke Fischer, but also so much more. I see it as a window into that particular sub-genre of detective-noir-quirky-add your own modifier here fiction. I’ve read it a number of times actually, and I keep finding new things in it.

Below, I will the first couple of pages of the introduction, and you can see for yourself what I’m talking about. Then if you’d like to grab yourself a copy of the new expanded edition, for a short time, I have both the ebook and paperback at a reduced price. But even if you don’t buy the book, I hope you enjoy this sample.

Not All Heroes Wear Fedoras

The modern detective novel is—like jazz and hip-hop—a peculiarly American invention. People are of course reading and writing them across the world now, and, much as they do for the other two artforms (European brass bands and French quadrilles mixed with traditional African folk songs in the case of jazz, Jamaican soundsystem culture’s influence on hip-hop), its roots lie elsewhere. The protozoan inklings of 20th century detective fiction can be seen in Sherlock Holmes and his continental counterpart Arsène Lupin, but it took a quintessential ‘Americanness’ to birth the gumshoe as we know it, splicing and dicing the old world DNA with another staunchly American figure – the cowboy.

We can argue over the exact moment of genesis, most likely a killer monkey in the cobblestoned streets of pre-Haussmann Paris, but let’s start with what is widely considered to be the Holy Trinity of modern detective fiction: Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Ross MacDonald. Shedding most—but not all—debonaire gentleman stylings (Philip Marlowe did enjoy poetry), the Holy Trinity transformed the detective into something thrillingly new: the Swingin’ Dick.

A private investigator both designed and equipped to scrutinize the modern world, moving between high and low registers of society, the Swingin’ Dick spoke in a native tongue informed by the angular syncopation of jazz. A language that became known as hard-boiled—cynical and sharp-edged, with an (at best) agnostic view of truth, justice, and the American way.

Yet despite this ambivalence, the Holy Trinity stuck to authority adjacent misfits with ingrained loyalties—however complicated—to the system. Marlowe came from the DA’s office. Lew Archer was once a cop. As for Dashiell Hammett, his Continental Op might have found employment as a Blackwater contractor in Iraq had he been born a century later.

Hammett’s later creation Sam Spade is perhaps the ne plus ultra Swingin’ Dick, a man who appears fully formed in 1930 then immortalized a decade later by Humphrey Bogart—as if he’d been sitting in his smoky dim-lit office since the dawn of time, blinds drawn, waiting for a leggy broad to wander in off the street with a sad story.

But the world changed in the years that came, and once we arrived at the sepia-toned upside down morality of the late sixties, the detectives had to adapt or perish. The next time we see Marlowe is in Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye, which dragged Chandleresque noir into LA’s sun-bleached 70s paranoia du jour.

A new generation of Swingin’ Dicks was born around this time, untethered from the institutions that had shaped their ancestors. Sure, Robert B. Parker’s Spenser used to be the fuzz, but he also bore witness to the moral quandary of the Korean War.

James Crumley’s Milo Milodragovich did too. Then he had a comfortable gig working matrimonial cases until no-fault divorce laws appeared, a reflection of a generational shift in social norms. The times were a-changin’—according to Bob Dylan anyway, the hard-boiled enfant terrible, the travelling troubadour of Swingin’ Dicks. In any event, it left this particular Dick swinging in the wind with no answers. Milo was eking out a living on the margins, hopped up on booze and pills. Still, he was positively angelic compared to Crumley’s subsequent hellhound CW Sughrue, a lunatic sumbitch who earned his stripes in the jungles of Vietnam.

Not all heroes wear capes, and by now they weren’t even wearing fedoras. They’d also grown distant from their European cousins, where detective novels were still largely dominated by the armchair mysteries of Miss Marple and Poirot.

Still, it wasn’t all Colonel Mustard and curtain twitchers. Georges Simenon’s Maigret brought a psychological acuity to the genre long before the tortured yet brilliant FBI profiler became a trope, while the French had been busy absorbing hard-boiled ‘Amerloque’ fiction, regurgitating it with a certain je ne sais quoi. The cross-pollination of American noir and nouvelle vague cinema through the 1960s is well documented, then Jean-Patrick Manchette burst onto the scene in 1971 with a new style of crime novel, drawing inspiration from the literary shift emerging across the Atlantic and infusing it with homegrown Situationist politics and the fierce existentialism of Camus.

The third and arguably most enduring member of Holy Trinity 2: Electric Boogaloo was John D. MacDonald with his idiosyncratic take on the Swingin’ Dick—Travis McGee. His origins are less clear, which is to be expected from someone whose sleuthing career is bookended by Beatlemania and Back To The Future. What we do know for certain is that he’s eschewed the office for a houseboat, operating as a ‘salvage consultant’ up and down the Florida coast with an eye-watering 50% commission fee.

Possessed with a cut-throat business model, McGee nevertheless rather presciently laments the environmental destruction of the Sunshine State by piranhic real estate developers and other assorted swindlers. This was years before world leaders were routinely jetting across the globe paying lip service to climate change.

Travis McGee is perhaps the most influential of the second wave Swingin’ Dicks. Everyone from Stephen King to Lee Child counts themselves as a fan, and he serves as the precursor to the Floridian crime fiction which followed—Carl Hiaasen’s sweltering madcap adventures, and the laconic swagger of Elmore Leonard, who began his pivot towards the Panhandle in the 1980s.

Crucially, while Travis is not adverse to bending or even breaking the rules for a higher purpose, he’s a lot more affable than his forebears while he does it. Simply put, he’s goddamn funny. An asshole, but a loveable one. Hard-boiled but hilarious.

Which brings us to Craig Terlson, whose own addition to the Swingin’ Dick canon Luke Fischer is spotted reading a Travis McGee paperback early on in Surf City Acid Drop. Clearly he’s a fan: “Now there’s a guy who knew how to do it.”

What are readers supposed to make of this baton-passing meta-wink? Is there any relevance to the fact that Fischer’s roots—like his creator—are in Canada? When it comes to crime fiction, what’s the difference between the American and Canadian sensibility anyway? Not a great deal, judging by this novel. The jokes still land much the same. Maybe they just have better healthcare.

Read the rest of Thomas Trang’s wonderful intro in the new expanded edition of Surf City Acid Drop. Out right now.

Great writing and I loved the presentation

What a great little treatise on the evolution of a genre!